Flight restriction impacts mental health.

Clipping or “trimming” wings affects more than just a bird’s feathers or even its body. Psychological well-being is, in many ways, just as important as physical well-being. As previously discussed, flight is a parrot’s primary means of locomotion. Thus, flight is its most natural way of responding to motivations and coping with its environment.1 The inability to respond to basic motivations due to anatomical restriction can lead to stress and the development of stereotypies, obsessive-compulsive behaviours, and self-mutilation. (Source: see footnote 1.) These kinds of behaviours can include pacing, rocking, screaming, feather-picking, and even biting.2 Birds who are clipped often perform behaviours and postures that indicate they have the urge to fly, but their owners may not recognise them as such. Some people argue that a bird clipped before fledging, who has never flown, “doesn’t know he can’t fly and doesn’t miss it”. How can you miss something you’ve never experienced? Simple: if it is an instinctual behaviour which you have been genetically programmed to do.

This clipped baby ringneck strains in a frustrated attempt to fly, demonstrating the deep instinctual urge that parrots have to move in this manner. It is not a coincidence that flight-restricted birds display this behaviour while fully flighted ones do not. Fortunately, his owner allowed his wings to grow out; they did not realise that the breeder would clip their bird in the first place. If you value full flight from fledging onward and do not want your bird clipped, it is important you make this clear to the seller since trimming wings is still the norm. Credit: @burdfeedz on Instagram.

This abnormal “wing-twitching” behaviour is undoubtedly the outward manifestation of a bird’s instinct and urge to fly. Not only do we see it in birds who are currently unable to fly, but it often immediately precedes flight in birds who have a history of flight restriction. To anyone experienced with developmentally normal flighted birds, this behaviour is painfully bizarre and distressing to behold. Credit: @the_green_bird_brigade on Instagram.

Animals—and humans–respond to stressful situations in a number of different ways. There are active coping strategies, such as fight or flight, and passive coping strategies, such as conservative withdrawal.3 Parrots are prey animals. It is in their nature to respond to threats by literally taking flight.4 When fleeing from a stressful situation is not possible, an animal who would typically choose flight may resort to fighting instead, much like the clipped birds who bite in situations where they would naturally be inclined to fly away. Some birds, depending upon their individual histories and personalities, may choose to surrender rather than fight when flight is not possible. A human might clip a fearful bird’s wings and assume that “tameness” has been achieved once the bird stops trying to get away. What has actually occurred is that the bird has entered a state of learned helplessness. Like I explained in my section on early development, learned helplessness is a condition where an animal or person is first confronted by inescapable stress or pain. Then, later on, even if it would be possible for them to escape the stress or pain, they don’t make any attempt to.5 A bird in such a situation, who has given up on trying to actively avoid the source of its stress, might resort to a passive coping strategy. Passive coping strategies are associated with much higher levels of anxiety than active ones. (Source: see footnote 3.) A bird who is able to choose the very natural and active coping strategy of flight, therefore, tends to be less anxious and more secure.

This amazon’s new owner captured a troubling display of how trimming wings does not remove the desire to fly. The bird looks about, bobs his head, and quivers his wings as much as to say, “I wish I could fly over there”. Trimming wings is often defended on the basis of safety but is simultaneously of great convenience for the human. Rather than training the bird and establishing a bird-friendly environment, the bird can simply be placed on a perch and left there until a human retrieves it. The choice is all in the human’s hands, an arrangement which contradicts what we now know about animal welfare. Physically disabled birds straining to fly but confined to perches represent no vast improvement over the permanently caged birds of the past. With all our modern knowledge of behaviour and training, we can do so much better than this. These animals do not want to sit in one place hour after hour. They want to experience choice, moving about their environment at will, receiving mental and physical stimulation. They want to fly. Credit: @birdstolove on Instagram.

Have you ever heard someone say that their bird is “better-behaved” while clipped? Trimming wings does not address unwanted behaviours; it seeks to circumvent and ignore them by forcing the bird into a state of physical dependence and psychological submission. Naturally, if a human is a bird’s only means of transportation—the only way to move throughout its environment, to escape the monotony of a perch, to see and do things—many birds in such a situation will eventually cooperate. Even if the bird is still inclined to bite certain individuals, as long as it cannot fly across the room to attack anyone, most people are content. And yet, what might an animal be experiencing psychologically when it ceases to be aggressive simply because it has lost all choice and control? What if the source of its aggression is past trauma, a stressor in its environment, or even hormonal urges exacerbated by inappropriate husbandry, yet the human has chosen to handicap it rather than address the root of the behaviour? What does it mean for us to take a highly intelligent animal and decide that it cannot even be afforded the ability to move normally within the confines of a single room? Studies have shown that any kind of active coping strategy can help relieve stress, even if it’s fighting with another animal, biting something, or self-grooming. (Source: see footnote 3.) It is not outlandish, therefore, to think that clipped birds may indeed experience stress because of their restricted mobility and that many undesirable behaviours, like plucking and biting, could be at least partially instigated by the need for active coping strategies.

This cockatoo’s previous owner clipped her wings as retaliation for biting them. Here, she strains and flaps in an attempt to fly. A year later, she has moulted only three feathers on each wing. Many people disable their birds via trimming wings as a way to give them an “attitude adjustment”. I can only hope that this stems from ignorance rather than malice. Parrots are wild animals. If expecting a perfect pet that requires little or no training, why not opt for something domesticated? Furthermore, I can think of no other animal which a person would strip of normal movement in response to an unwanted behaviour. Credit: @featheredfeckers on Instagram.

To quote an article published in the Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine, “It is an accurate oversimplification to say that most behavioral FDB [feather destructive behaviour] is related to a reductive environment over which the bird has little or no control.”6 There are many factors which can contribute to the development of this disorder, but the loss of flight does carry with it a significant loss of control which infringes upon a bird’s ability to respond to motivations and cope with its environment. One study on African greys found that birds who were unable to fly were five times more likely to engage in feather-picking behaviour.7 Another study did not find a statistically significant relationship between clipped wings and feather-picking, but it did find that cockatoos from pet stores were six times more likely to feather-pick than those from private breeders. The authors hypothesised that this could be due to factors such as lack of stimulation in the pet store environment.8 Given that the avian brain has evolved to respond to the visual processing challenges associated with flight9, and that regions responsible for spatial and pattern discrimination reach higher activity levels during flight10, 11, it seems reasonable to assume that a truly flighted lifestyle would promote higher levels of brain stimulation.

This 20-year-old conure was clipped for the first ten years of her life. Two years after her flight feathers grew in, she would attempt flight only when spooked and would quickly land on the ground. Five years after her flight feathers grew in, she would still attempt flight only when spooked but could complete 1-2 laps around the room before tiring. She has had all of her flight feathers for about ten years now, but she will still only fly when spooked or during recall training, which she started about a year ago. This video demonstrates how hesitant the bird is to execute a natural behaviour which she had previously shown to be capable of while frightened. Once she could accomplish a tiny hop, her owner increased the distance gradually–the farthest she can now fly during training is three feet. This bird, who had been plucking for ten years, has stopped plucking altogether since improving her flight ability through recall training. Credit: 1Tale4Paws on Youtube and Instagram.

Merely having unclipped wings does not necessarily imply a flighted lifestyle, either. An unclipped bird may be kept under circumstances which allow for precious little flight opportunity. Many pet birds are clipped before fledging, which hampers their willingness and ability to fly later in life, particularly if they are larger or heavy-bodied birds like the cockatoos and African greys used in the aforementioned study. Therefore, the relationship between flight restriction and FDB may not be uncovered on the basis of clipped versus unclipped wings alone, though there is a physical component to the clipped feathers that may serve as a gateway to this disorder. Dr. Marie Kubiak, specialist in zoo and wildlife medicine, points out that the discomfort caused by clipped feather ends rubbing against a bird’s body can serve as a trigger for FDB, and that trimming wings “compromises flight, an essential parrot behaviour”.12

This Hahn’s macaw, age unknown, was clipped and confined to a cage before coming to his new home. Although his flight feathers are growing back in, he was previously clipped completely, with the entire wing matching the level of the clipped feathers currently seen. This bird’s avian vet believes that the trimming of wings, along with a lack of enrichment, played a significant role in the development of his feather destructive behaviour (in this case the barbering and snapping of feathers). An update on the same bird appears immediately below. Credit: @flightedfeathers on Instagram.

There are countless stories of people clipping their flighted birds and immediately noticing a personality change. Owners of these birds usually describe them as depressed. Sadly, when people in this position ask for help, they are often met with comments insisting that the bird will “get over it” and to “just give it time”. If you gradually learned to cope with a new injury or disability, would it be fair to say that you “got over it” and that you didn’t ever want your mobility back? A case study on an eight-year-old cockatiel presented for lethargy, watery droppings, and decreased appetite revealed, after blood tests and X-rays, that the bird was not suffering from a disease. The bird’s owner had recently requested a nail trim at a pet store and, not surprisingly, the employee had also clipped his wings as a matter of routine, even though the owner had not requested it. The veterinarians suspected that the bird’s muscle enzyme elevations were due to attempting to fly and crashing into the ground again and again, while his elevated glucose and watery droppings were likely due to stress.13 This is the manner in which a bird is expected to “get over” its new handicap: repeatedly failing at executing a natural behaviour until it gives up trying.

The person who purchased this baby cockatiel was shocked to see how punishing it was for her to attempt flight. This bird was purchased at a store and was given the clip seen on so many birds that intends to eliminate all flight. While it is true that this is a severe clip, it is a very common one. And, while it may be difficult to watch a bird struggle in this manner, I hope it will allow some people to see clipped birds in a new light. Flight is natural and birds have the inborn desire to attempt it. The fact that a larger bird like an Amazon, cockatoo, or macaw may merely strain or shuffle when clipped rather than leap and fall should be no less disturbing. Credit: Alicia K.

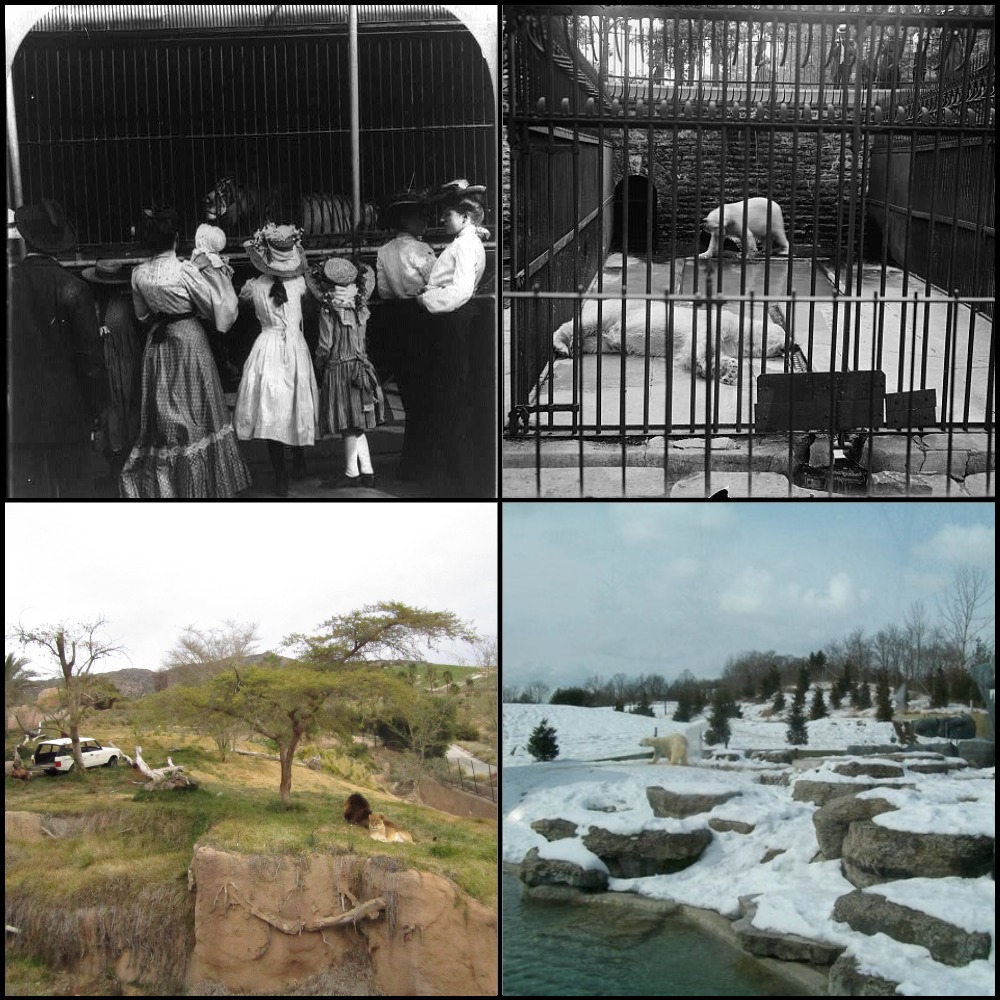

I wanted to discuss animal welfare in this section because mental and emotional health, not just physical health, are now considered major criteria for evaluating how well an animal is doing in a captive environment.14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 Strategies for keeping animals in captivity are progressively including more and more considerations for natural behaviours and habitats (source: see footnotes 14, 15, and 16), as well as the element of choice (footnote 18), to provide the best conditions possible. Researchers have found that offering animals choices has positive effects, decreasing both stress and the incidence of abnormal behaviours, even if the animals don’t act on the choices provided. (Source: see footnote 18.) A 2018 guide on zoo animal welfare recommends that enclosures “provide for a range of species-appropriate behaviours (e.g., flight, swimming, climbing, and digging)”. (Source: see footnote 16.)

If you lived during the early 1900s and suggested that the cages pictured at top might have negative effects on the animals’ psychological well-being, you probably would have been laughed at. Likewise, some people today scoff at the idea that a bird suffers mental detriments when deprived of normal locomotion. You will hear arguments supposedly couched in science that demand research proving birds need to fly (while providing no research proving that they don’t). It is not scientific, however, to argue that millions of years of evolution and biological adaptations are insignificant merely because accommodating flight is more work for people than trimming wings. Images from the Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons, and TripAdvisor.21

A 2014 paper in the International Zoo Yearbook stresses that “…there is a growing trend towards providing animals with more naturalistic settings that allow and encourage them to perform species-specific behaviours to the greatest degree possible. This evolution necessitates holding flying birds in aviaries, because only when birds are kept full winged are they able to exhibit a reasonable representation of their behavioural repertoire correctly.” (Source: see footnote 19.) Our birds may live with us rather than in zoos, but they are still wild animals. They are still naturally flighted animals. Trimming wings may appear acceptable because it is so common, but there are countless ways we used to keep wild animals in captivity–which seemed perfectly appropriate to people at the time–which are no longer considered legitimate. Trimming wings may also appear acceptable because the birds “seem fine”—but animal welfare can be very poor even in the absence of obvious behavioural signs. (Source: see footnote 17.) Thus, we cannot know the full extent of psychological stress a bird experiences due to the restriction or deprivation of flight, but it would be absurd to assume that one of the planet’s most intelligent animals20 is content without its mobility. As I said in my section “Built For Flight“: do we really need a study to prove that flight should be an indispensable facet of a naturally flighted bird’s life in captivity?

This macaw, who was clipped for over twenty years, never so much as opened his wings before his new owner began flapping exercises with him. Once his muscles regained some strength, he began to flap on his own. Just because a bird does not flap or attempt to fly does not mean that they “don’t care they can’t fly” or “don’t want to fly”. After being clipped for such a long time, their muscles become atrophied and they physically cannot flap without great effort or even pain. Mentally, they have little to no conscious awareness of how to fly, particularly if clipped before fledging, though the desire is there. There is no video I can show you that perfectly illustrates psychological stress due to this form of handicapping. I can only show you how birds, in sometimes small and subtle ways, tell us they would not choose this. All clipped birds would have been flyers if they had not been clipped, barring some kind of deformity or medical condition. Credit: 1Tale4Paws on Youtube and Instagram.

If you have been reading each of the sections on this website in order, consider all the evidence I have supplied you with thus far and ask yourself: is it more likely that flight is beneficial and that trimming wings invites harmful effects, or is it more likely that trimming wings is harmless? Does the burden of proof lie with those who do not wish to alter the animal’s normal movement, or with those who do? If you find yourself wishing to keep flighted birds but are unsure of how to do this, please read on to the “Flight in the Home” and “Training” sections of this site.

Clipping is not necessary to keep birds safe around the house!

References

- Speer, B., 2015. Current Therapy in Avian Medicine and Surgery. Elsevier Health Sciences, p. 694. https://books.google.com/books?id=LKY_CwAAQBAJ

- Jenkins, J.R., 2001. Feather picking and self-mutilation in psittacine birds. Veterinary clinics of North America: Exotic animal practice, 4(3), pp.651-667. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1094919417300294

- Steimer, T., 2011. Animal models of anxiety disorders in rats and mice: some conceptual issues. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 13(4), p.495. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3263396/

- Van den Hout, P.J., Mathot, K.J., Maas, L.R. and Piersma, T., 2009. Predator escape tactics in birds: linking ecology and aerodynamics. Behavioral Ecology, 21(1), pp.16-25. https://academic.oup.com/beheco/article/21/1/16/179705

- Song, L., Che, W., Min-Wei, W., Murakami, Y. and Matsumoto, K., 2006. Impairment of the spatial learning and memory induced by learned helplessness and chronic mild stress. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 83(2), pp.186-193. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0091305706000086

- Rubinstein, J. and Lightfoot, T., 2012. Feather loss and feather destructive behavior in pet birds. Journal of exotic pet medicine, 21(3), pp.219-234. https://www.vetexotic.theclinics.com/article/S1094-9194(13)00089-3/pdf

- Schmid, R., Doherr, M.G. and Steiger, A., 2006. The influence of the breeding method on the behaviour of adult African grey parrots (Psittacus erithacus). Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 98(3-4), pp.293-307. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0168159105002947

- Jayson, S.L., Williams, D.L. and Wood, J.L., 2014. Prevalence and risk factors of feather plucking in African grey parrots (Psittacus erithacus erithacus and Psittacus erithacus timneh) and cockatoos (Cacatua spp.). Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine, 23(3), pp.250-257. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1557506314001062

- Shimizu, T., Shinozuka, K., Uysal, A.K. and Kellogg, S.L., 2017. The origins of the bird brain: multiple pulses of cerebral expansion in evolution. In Evolution of the Brain, Cognition, and Emotion in Vertebrates (pp. 35-57). Springer, Tokyo. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-4-431-56559-8_2

- Gold, M.E.L., Schulz, D., Budassi, M., Gignac, P.M., Vaska, P. and Norell, M.A., 2016. Flying starlings, PET and the evolution of volant dinosaurs. Current Biology, 26(7), pp.R265-R267. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S096098221630077X

- Watanabe, S., Mayer, U. and Bischof, H.J., 2011. Visual Wulst analyses “where” and entopallium analyses “what” in the zebra finch visual system. Behavioural brain research, 222(1), pp.51-56. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0166432811002269

- Kubiak, M., 2015. Feather plucking in parrots. In Practice, 37(2), pp.87-95. https://inpractice.bmj.com/content/37/2/87

- Graham, J., n.d. Flight Trouble: To Trim or Not to Trim. Tufts University. https://sites.tufts.edu/progressnotes/2015/01/flight-trouble-to-trim-or-not-to-trim/

- Animal Welfare Committee, n.d. Association of Zoos & Aquariums. https://www.aza.org/animal_welfare_committee

- Wolfensohn, S., Shotton, J., Bowley, H., Davies, S., Thompson, S. and Justice, W., 2018. Assessment of welfare in zoo animals: Towards optimum quality of life. Animals, 8(7), p.110. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6071229/

- Sherwen, S., Hemsworth, L., Beausoleil, N., Embury, A. and Mellor, D., 2018. An animal welfare risk assessment process for zoos. Animals, 8(8), p.130. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6116011/

- Jordan, B., 2005. Science-based assessment of animal welfare: wild and captive animals. Revue Scientifique Et Technique-Office International Des Epizooties, 24(2), p.515. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/ce97/706152f65ccec752236edd29ca74a859ee8f.pdf

- Laura, M.K., 2015. Choice and control for animals in captivity. Psychologist, 28, pp.892-895. https://thepsychologist.bps.org.uk/volume-28/november-2015/choice-and-control-animals-captivity

- Bračko, A. and King, C.E., 2014. Advantages of aviaries and the A viary D atabase P roject: a new approach to an old housing option for birds. International zoo yearbook, 48(1), pp.166-183. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259550442_Advantages_of_aviaries_and_the_Aviary_Database_Project_A_new_approach_to_an_old_housing_option_for_birds

- Olkowicz, S., Kocourek, M., Lučan, R.K., Porteš, M., Fitch, W.T., Herculano-Houzel, S. and Němec, P., 2016. Birds have primate-like numbers of neurons in the forebrain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(26), pp.7255-7260. https://www.pnas.org/content/113/26/7255

- Lion, early 1900s: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2015645135/; Polar bears, early 1900s: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2016813663/; Lion habitat, San Diego Zoo Safari Park: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lion_Camp_2.JPG; Polar bear habitat, Toronto Zoo: https://www.tripadvisor.com/LocationPhotoDirectLink-g155019-d186704-i62326906-Toronto_Zoo-Toronto_Ontario.html